The Western film genre is defined by wide-open landscapes, solitary antiheroes, tense standoffs, and stark morality. Yet, few films have so thoroughly reshaped and embodied the genre as The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966). Directed by Sergio Leone and powered by Ennio Morricone’s iconic score, this film has not only achieved cult status but redefined the very tenets of Western storytelling for generations worldwide. Examining its narrative architecture, aesthetic techniques, cultural influence, and ongoing legacy reveals why it is often considered the ultimate Western.

A Revolutionary Approach to Storytelling

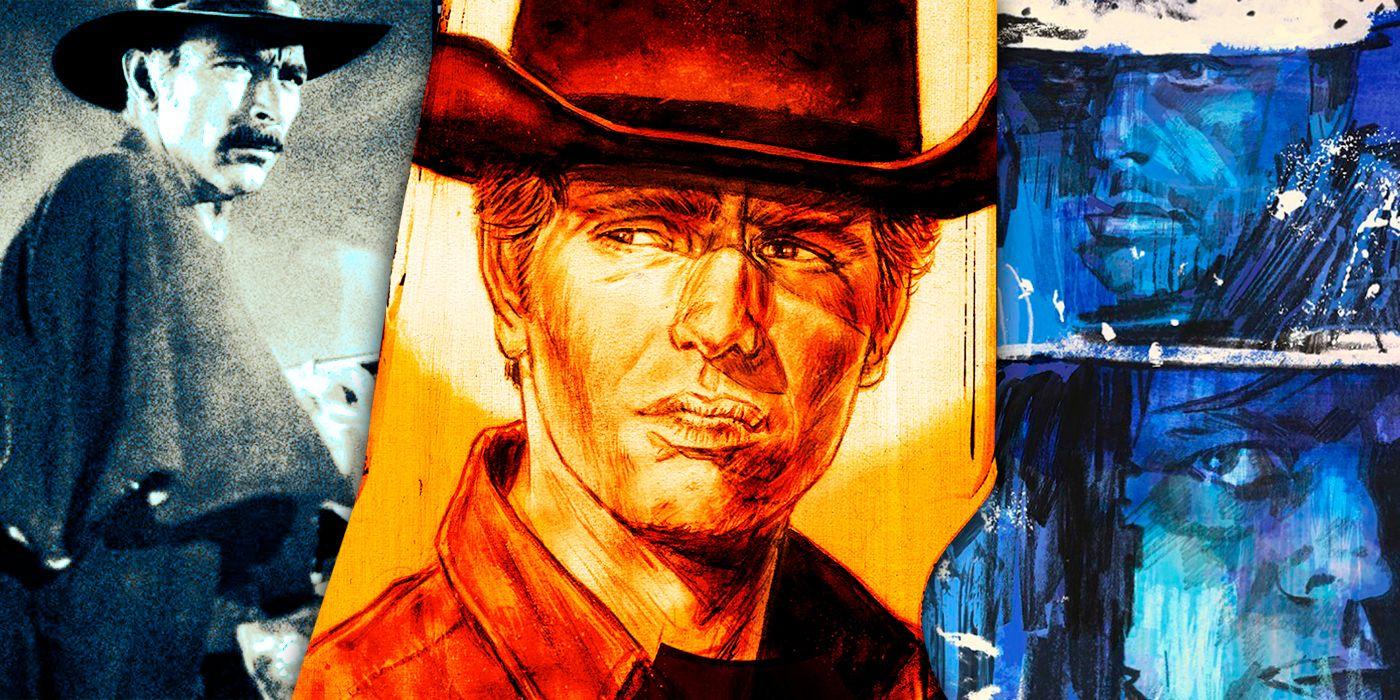

At its core, the film’s genius lies in Sergio Leone’s fearless subversion of traditional character archetypes. Here, the lines between heroism and villainy are artfully blurred. The trio—Blondie (the Good), Angel Eyes (the Bad), and Tuco (the Ugly)—represent not just straight moral opposites, but complex, flawed, and unpredictable individuals. None embody the pure-hearted cowboy or purely evil outlaw familiar from earlier Westerns. Instead, each character is guided by survival instincts, greed, and a unique personal code.

Leone structures the plot around a treasure hunt during the American Civil War, using the larger conflict as a backdrop rather than the focal point. This enables the director to spotlight the personal journeys and transformations of the central characters. The narrative interweaves their motivations and allegiances, culminating in a legendary three-way standoff—a set piece now imitated countless times across cinema.

Visual Narratives and Memorable Filmmaking

Leone’s visual sensibility is revolutionary for its time. The director’s use of extreme close-ups juxtaposed with vast landscape vistas creates an experiential tension unique to the film. Cinematographer Tonino Delli Colli employs natural light to accentuate the dust, sweat, and grit etched into each character’s visage, enhancing realism while also building mythic resonance.

Perhaps the movie’s most renowned visual segment is its finale at Sad Hill Cemetery. With swift cuts, changing viewpoints, and an agonizingly extended quiet, Leone crafts an almost unbearable tension. The interplay of gazes and gestures preceding the gunshots isn’t just dramatic flair; it’s a manifestation of psychological combat, forever reshaping how cinematic shootouts are envisioned.

Rewriting the Soundscape: Ennio Morricone’s Score

If Leone reimagined the visual lexicon of Westerns, Ennio Morricone fundamentally altered their auditory landscape. The central musical motif of the movie, distinguished by its coyote-esque cries, eerie whistles, and unconventional instrumentation, stands as one of the most iconic scores ever created. This musical composition transcends mere accompaniment; it operates as a driving narrative element, intensifying feelings, delineating personalities, and occasionally even punctuating the unfolding events with a theatrical magnificence.

Morricone’s musical compositions for every principal character—a distinctive whistle for Blondie, a melodic flute for Angel Eyes, and expressive human voices for Tuco—function as aural leitmotifs, deepening their portrayal and inner lives without requiring explanatory conversation. The collaborative effort between the director and the composer in this movie established a lasting standard for the fusion of music and cinematic art.

Moral Ambiguity and the Frontier Myth

Most earlier Western films idolized the frontier, casting the West as a place where good could triumph over evil in a lawless environment. Leone’s film challenges this myth, presenting the Union and Confederate armies not as paragons of virtue or villainy, but as institutions capable of senseless violence and corruption. The futility and chaos of war loom constantly in the background, rendering the treasure hunt both absurd and existential.

The intricate ethical dilemmas faced by the central characters highlight the subtle boundary separating virtue and vice when driven by self-preservation and avarice. This inherent uncertainty provides a more genuine portrayal of the human experience, prompting viewers to challenge rigid moral frameworks and the straightforward heroism often found in traditional Westerns. Under Leone’s direction, the American frontier transforms into a symbolic representation of life’s unpredictability, perils, and moral complexities.

Influence and Imitation: Setting the Standard

The movie’s impact extends beyond its category. Filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino, Martin Scorsese, and the Coen Brothers have acknowledged its foundational role. The “Mexican standoff”—made famous by the graveyard finale—is now a worldwide cinematic symbol for suspense, deception, and fluctuating authority.

In addition, the movie spawned the “spaghetti Western” subgenre, influencing numerous European and American works that embraced Leone’s distinctive stylistic and thematic elements. The raw authenticity, anti-heroic figures, and intricate moral dilemmas became defining characteristics, ultimately permeating American neo-Westerns, reinterpreted narratives, and even diverse genres, ranging from science fiction to graphic novels.

On a technological level, Leone’s experimental editing, use of widescreen Techniscope format, and innovative blending of soundtracks laid the groundwork for modern action cinema, influencing editing rhythms and sound design in contemporary blockbusters.

A timeless film

Multiple layers of artistry converge in The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. The film’s narrative intricacies, psychological characterization, visual grandeur, and sonic ingenuity form a holistic cinematic experience. Its commentary on violence, morality, and the unpredictability of fate resound even beyond its Western backdrop, offering a timeless meditation on human nature and power.

Through relentless innovation and fearless storytelling, Leone’s masterpiece refuses to fade into nostalgia. Instead, it endures as a touchstone—one that continues to challenge, entertain, and inspire. As each new generation re-engages with its dust-blown duels and existential questions, the film remains not just a pinnacle of Western cinema, but a landmark in the global language of film itself.